Absorption — what it means and why it matters

Some pills never make it into your bloodstream the way you expect. Absorption is the step when a drug moves from the place you take it (like your gut or skin) into your blood. How fast and how much of a drug gets absorbed changes how well it works and how long it lasts. That’s called bioavailability.

Think of absorption like a gate. The gate can be wide open, half-closed, or blocked by food, other drugs, your stomach acid, or even supplements. Small changes at the gate can turn a good dose into a weak one — or into too much of a drug, which raises the risk of side effects.

Common things that change absorption

Food: Taking some meds with food helps (fat helps absorb fat-soluble drugs). Other drugs work best on an empty stomach. For example, levothyroxine (Synthroid) is famously affected by food, calcium, and iron — take it separately and usually before breakfast.

Acid and stomach pH: Antacids, proton-pump inhibitors, and H2 blockers raise stomach pH and can reduce absorption of drugs that need acid. Some antifungal pills and certain cancer drugs fall into this group.

Other medicines and grapefruit: Grapefruit and grapefruit juice block an enzyme (CYP3A4) in the gut. That can raise levels of drugs that the enzyme normally breaks down, sometimes dangerously so. Antibiotics, heart meds, and some psychiatric drugs are examples — always check warnings.

Binding substances: Calcium, iron, bile-acid binders, and some antacids can bind certain meds and stop them from being absorbed. That’s why spacing doses by a few hours matters.

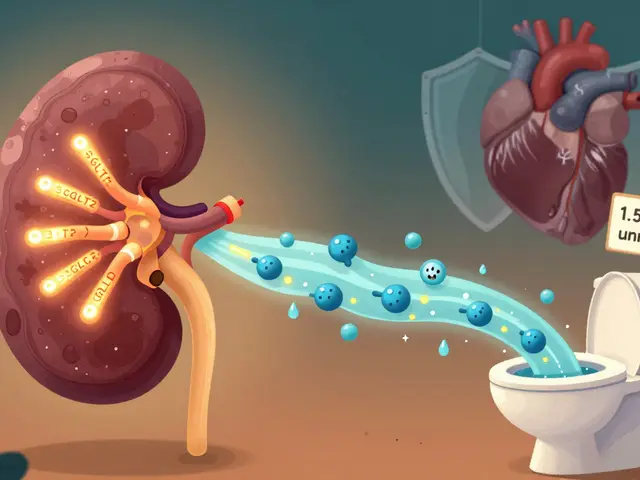

Formulation and route: Liquid forms and immediate-release tablets hit the blood faster. Extended-release or enteric-coated pills release slowly or skip stomach acid, changing both speed and amount absorbed. Injections and IVs bypass absorption entirely and put the drug straight into the blood.

Practical tips to keep absorption predictable

Read the label and follow directions: If a medicine says "take on an empty stomach," that usually means one hour before or two hours after food. If it says "with food," eat something that matches the drug’s needs (some need fat, some need any food).

Space supplements and interacting drugs: Take calcium, iron, and multivitamins a couple of hours away from thyroid meds, certain antibiotics, and others that bind minerals. When in doubt, separate by 2–4 hours.

Avoid grapefruit unless your doctor says it’s safe. Ask about antacids and acid reducers if you take long-term treatment for heartburn — they can change how other drugs work.

Keep a short list: Carry a simple list of prescription meds, OTCs, and supplements. Share it with every provider and your pharmacist. They can flag absorption problems like drug interactions or poorly timed doses.

Want more detail? Read our articles on pancrelipase for digestion and absorption, erythromycin and timing, or the Synthroid cost and timing guide to see real examples and tips from everyday people.

Small timing changes and a few questions to your pharmacist can make a huge difference in how well your meds work. Pay attention to instructions, and speak up if something doesn’t seem to be working.

Ibrutinib Pharmacokinetics: What Happens After You Take the Pill?

Curious how ibrutinib works once you swallow it? This article explains what your body does with ibrutinib, how long it sticks around, and how things like food or other medications may affect it. We’ll break down its journey from your stomach to your bloodstream and beyond, plus share some practical tips for anyone taking ibrutinib or caring for someone who does. This info can help you make sense of lab results or side effects. No complicated science talk—just the details you actually need.

read more