When you take a generic drug, you expect the same safety and effectiveness as the brand-name version. But here’s the problem: serious adverse events from generic drugs are consistently underreported - and that gap in data could be putting patients at risk.

What Counts as a Serious Adverse Event?

A serious adverse event (SAE) isn’t just a mild side effect. It’s something that can change your life - or end it. The FDA defines it as any reaction that is:

- Death

- Life-threatening

- Requires hospitalization

- Causes permanent disability

- Leads to birth defects

- Needs medical intervention to prevent lasting harm

This applies to any drug - brand or generic. If you take a generic version of losartan and end up in the ER with a severe allergic reaction, that’s an SAE. It doesn’t matter that it’s not the name you recognize on the TV ad. The rules are the same. But the reporting? Not even close.

Same Rules, Different Reality

Legally, generic manufacturers must report serious and unexpected adverse reactions to the FDA within 15 days. They must keep records for 10 years. They use the same MedWatch Form 3500. The process is identical on paper. But in practice? It’s broken.

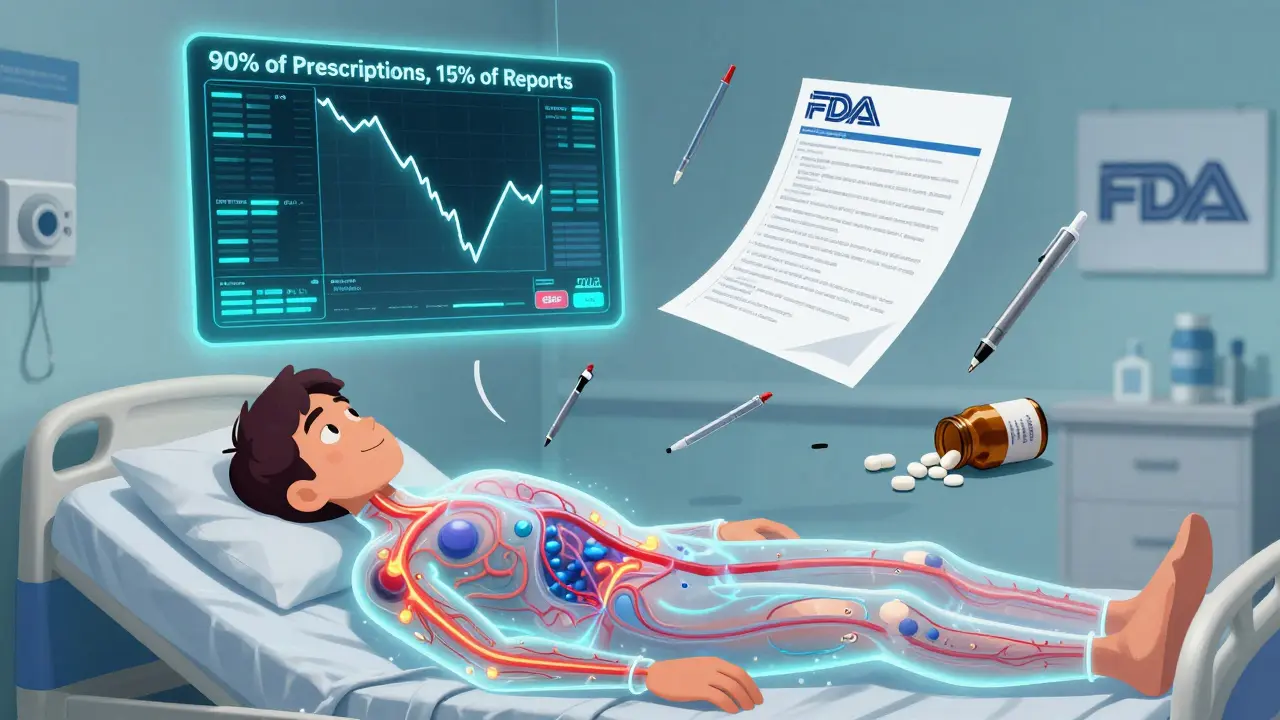

Here’s the hard truth: generic drugs make up about 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. Yet, they account for less than 15% of serious adverse event reports. Meanwhile, brand-name drugs - which account for just 1% of prescriptions - generate nearly 70% of those reports. That’s not a coincidence. It’s a system failure.

Why? Because the system was built around brand-name drugs. Big pharma companies have entire teams dedicated to tracking side effects. They monitor every report, investigate every pattern, and file detailed submissions. Generic manufacturers? Many are small companies with no pharmacovigilance staff. Some outsource it. Others ignore it. A 2022 survey found only 42% of generic drugmakers have dedicated safety teams. The rest? They’re flying blind.

The Bottle Problem: Who Made This Pill?

Here’s where it gets messy for healthcare providers. You see a patient with a serious reaction. You ask, “What generic did you take?” They look at the bottle. The label says “Losartan 50 mg.” No manufacturer name. No logo. Just a code.

That’s not an accident. Pharmacies switch generic suppliers constantly to save money. One week, it’s Teva. Next week, it’s Amneal. The patient doesn’t know. The pharmacist doesn’t always know. And the FDA’s system? It needs the manufacturer name to connect the dots.

A 2020 survey by the Institute for Safe Medication Practices found 68% of healthcare providers struggled to identify the generic manufacturer when filing a report. Compare that to 12% for brand-name drugs. That’s why 42% of providers abandon generic SAE reports entirely - they can’t fill out the form correctly.

And it’s not just doctors. Pharmacists, nurses, even patients themselves are left guessing. A family physician in Texas told me he once reported a reaction to “Synthroid” - the brand - because the patient couldn’t tell him which generic they’d been given. The report was wrong. The data was useless.

What’s Being Done? The Slow Fix

The FDA knows this is a problem. In 2023, they launched FAERS 2.0 - an upgraded version of their adverse event database that can now link reports to specific National Drug Code (NDC) numbers. That’s huge. NDC codes are unique to each manufacturer and batch. If you can capture that at the pharmacy counter, you can trace a reaction back to the right company.

But here’s the catch: pharmacies don’t currently capture NDC codes on prescriptions. The FDA is pushing for it. In June 2023, they released draft guidance asking pharmacies to print the manufacturer name on every generic prescription label. Simple. Direct. Effective.

Some hospitals are already ahead of the curve. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists recommends barcode scanning at the point of administration. One pilot study showed that when nurses scanned the pill bottle before giving it to a patient, generic adverse event reporting accuracy jumped by 63%. That’s not a minor improvement. That’s a game-changer.

The FDA’s 2024 pilot program with major pharmacy chains aims to automate this. Imagine: you walk out of CVS with your generic metformin. The scanner reads the NDC. That data goes straight into the pharmacy’s system. If a patient reports a reaction six months later, the system pulls up the manufacturer - no guesswork needed.

Why This Matters Beyond the Numbers

This isn’t just about filling out forms. It’s about safety.

Generic drugs are chemically identical to brand-name versions - but they’re not always the same. Differences in fillers, coatings, or manufacturing processes can affect how a drug is absorbed. That’s why some patients have bad reactions to one generic but not another. The FDA calls these “bioequivalence gaps.” They’re rare. But when they happen, they’re dangerous.

Without accurate reporting, we can’t detect these patterns. A 2018 study on losartan showed a spike in adverse event reports after generics entered the market - but no one knew why. Was it the drug? The manufacturer? The batch? We still don’t know. That’s the cost of underreporting.

Dr. Daniel Korn of the FDA put it plainly: “The underreporting of adverse events for generic drugs creates a significant gap in our post-marketing surveillance system.”

And if we don’t fix this? The Government Accountability Office warns we could miss 15 to 20 dangerous safety signals every year by 2030. That’s not theoretical. That’s real patients - people like your neighbor, your parent, your sibling - who could be harmed because no one knew what they were taking.

What You Can Do

If you take generic drugs, here’s what you need to do:

- Check the label. Look for the manufacturer name. It’s often printed in small type on the bottle or the pill itself.

- Keep the bottle. Don’t throw it out. If you have a reaction, you’ll need to know who made it.

- Ask your pharmacist. If you’re switching generics, ask: “Is this the same manufacturer as last time?”

- Report it. If you have a serious side effect, tell your doctor. Ask them to file a MedWatch report. If they don’t know how, direct them to the FDA’s online portal.

If you’re a healthcare provider:

- Always record the manufacturer name - even if you have to look it up in DailyMed using the NDC code.

- Advocate for barcode scanning in your clinic or hospital.

- Don’t assume the patient knows. Don’t assume the pharmacy knows. Verify.

What’s Next?

The industry is waking up. Generic drug manufacturers are spending more on safety systems - from $185 million in 2023 to an expected $320 million by 2027. GDUFA III (the FDA’s generic drug funding program) has allocated $15 million specifically for improving post-market safety monitoring.

But technology alone won’t fix this. It takes culture. It takes accountability. It takes every person who handles a generic drug - from the pharmacist to the patient - understanding that this isn’t just paperwork. It’s protection.

When you take a generic, you’re trusting that the system works. Right now, it doesn’t - not fully. But it can. And it has to.

Do generic drugs have the same safety profile as brand-name drugs?

Legally, yes - they must meet the same bioequivalence standards as brand-name drugs. But in practice, differences in inactive ingredients, manufacturing processes, or packaging can lead to variations in how the drug performs in some patients. The bigger issue is that adverse events from generics are underreported, so we don’t have complete safety data. That means we might miss subtle but dangerous differences between generic versions.

Who is responsible for reporting serious adverse events from generic drugs?

The manufacturer of the generic drug is legally required to report serious and unexpected adverse events to the FDA within 15 days. Healthcare providers and patients can also report through the FDA’s MedWatch system. However, many reports are filed under the brand name because the patient or provider doesn’t know which generic manufacturer produced the drug.

Why is it hard to report adverse events for generic drugs?

The main issue is identifying the manufacturer. Generic drugs are often sold without clear branding, and pharmacies switch suppliers frequently. Patients rarely know which company made their pills. Reporting forms require the manufacturer name, and without it, providers often skip the report or file it under the brand name - which distorts the data.

Can I report an adverse event if I don’t know the generic manufacturer?

Yes. If you don’t know the manufacturer, report the event anyway. Use the generic name (e.g., “amlodipine”) and note that the manufacturer is unknown. The FDA can still analyze the pattern. You can also call your pharmacist or check the pill bottle - the manufacturer name is often printed on the label in small text. If all else fails, report using the brand name and add a note: “Patient took generic equivalent.”

Are there tools to help identify the manufacturer of a generic drug?

Yes. The National Library of Medicine’s DailyMed database lets you search by National Drug Code (NDC), which is printed on prescription labels. Many hospitals now use barcode scanners at the point of dispensing to automatically capture manufacturer data. Pharmacies are also starting to include manufacturer names on labels - a change the FDA is pushing for nationwide.

How does the FDA use adverse event reports for generic drugs?

The FDA uses these reports to detect safety signals - patterns of unexpected reactions that may indicate a problem with a specific manufacturer, batch, or formulation. If enough reports point to the same issue, the FDA can issue warnings, request label changes, or even investigate manufacturing practices. But without accurate data, these signals get lost.

What’s being done to fix underreporting of generic drug adverse events?

The FDA is rolling out FAERS 2.0, which links reports to NDC codes. They’re also pushing pharmacies to print manufacturer names on all generic prescriptions. A 2024 pilot program with major pharmacy chains aims to automate this data capture at the point of dispensing. Meanwhile, GDUFA III funding is increasing resources for generic drug safety monitoring. But progress is slow - and depends on both industry action and patient awareness.

15 Comments