Isoniazid is one of the most widely used drugs in the world for treating and preventing tuberculosis. It’s cheap, effective, and has been saving lives since the 1950s. But for many people, especially those on combination therapy, it comes with a hidden risk: liver damage. This isn’t rare. About 1 in 5 patients taking isoniazid will show signs of liver stress, and in some cases, it can be severe enough to stop treatment entirely. The problem isn’t just the drug itself-it’s how it reacts with other medications, your genes, and your lifestyle.

Why Isoniazid Can Hurt Your Liver

Isoniazid doesn’t damage the liver directly. It’s broken down in the body into toxic byproducts, and how quickly your body clears those byproducts determines your risk. That speed depends on an enzyme called NAT2, which is controlled by your genes. About half of people of European or North American descent are slow acetylators-meaning their NAT2 enzyme works slowly. In South Africa, that number jumps to nearly 90%. These people build up more of the harmful metabolites, like acetylhydrazine, which attack liver cells. The result? Liver enzymes rise. In mild cases, you might not even feel anything. But in 20-25% of patients, ALT and AST levels climb above normal. Some develop nausea, vomiting, or pain in the upper right abdomen. Jaundice, dark urine, or pale stools mean the damage is worsening. In rare cases, acute liver failure happens. The good news? Most people recover fully if the drug is stopped early.How Rifampin Makes Things Worse

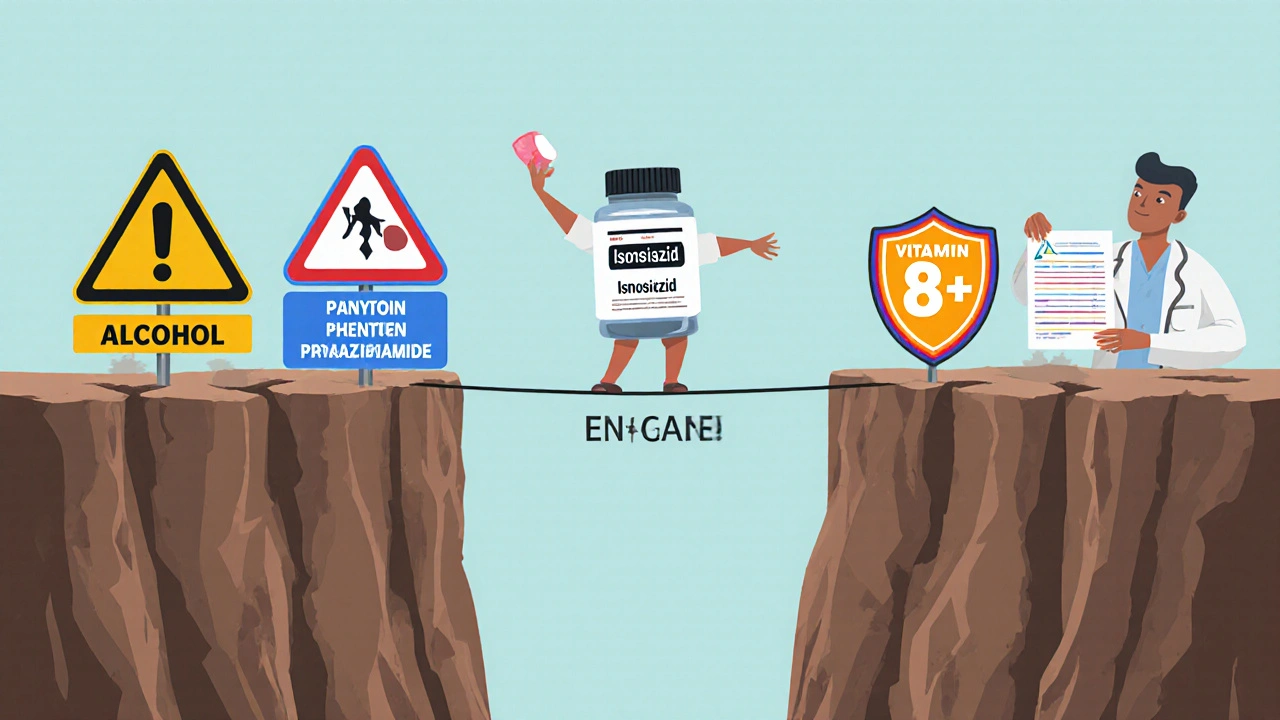

Isoniazid is rarely used alone. For active tuberculosis, it’s almost always paired with rifampin, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol. That’s the standard HRZE regimen. But combining isoniazid with rifampin doubles the risk of liver injury. Why? Rifampin turns on liver enzymes-especially CYP2E1 and CYP3A4-that convert isoniazid into even more toxic chemicals. It’s like turning up the heat on a slow-burning fire. Studies show that when taken together, the chance of liver damage jumps from 2-5% with isoniazid alone to 5-15% with the combination. One 2019 study found rifampin increased acetylhydrazine levels by up to 40% in slow acetylators. That’s why the American Thoracic Society calls this combination an “idiosyncratic metabolic reaction”-a chemical storm triggered by the two drugs working against each other.Pyrazinamide Adds Fuel to the Fire

Pyrazinamide, the third drug in the standard TB regimen, isn’t innocent either. It’s independently linked to liver injury, especially in people who already have risk factors like alcohol use or pre-existing liver disease. When you stack all three-isoniazid, rifampin, and pyrazinamide-the risk hits 10-20%. That’s why some guidelines now favor a 4-month regimen with rifampin and isoniazid only (HR), which cuts liver injury risk by nearly half. The CDC and WHO now recommend the shorter 4-month regimen for drug-susceptible TB, especially in older adults or those with liver concerns. It’s not just about effectiveness-it’s about safety. Fewer months on isoniazid means less time for toxic metabolites to build up.Other Drugs That Clash With Isoniazid

Isoniazid doesn’t just team up with TB drugs to cause trouble. It also interferes with many common medications by blocking liver enzymes. If you’re taking phenytoin for seizures, carbamazepine for bipolar disorder, or even some antidepressants like fluoxetine, isoniazid can cause those drugs to build up in your blood. One study showed phenytoin levels rose by 55% in patients on isoniazid. That’s dangerous-it can lead to dizziness, confusion, or even seizures. Even alcohol is a problem. People who drink more than 14 drinks a week (for men) or 7 for women have a much higher risk of liver injury. Alcohol also activates CYP2E1, the same enzyme that turns isoniazid into poison. So if you’re on isoniazid and you drink, you’re essentially doubling your exposure to toxins.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Not everyone is equally vulnerable. Here’s who needs extra caution:- Slow acetylators-People with two copies of the slow NAT2 gene. This includes most East Asians, South Africans, and many Europeans.

- People over 50-Liver function slows with age, and detox capacity drops.

- Those with existing liver disease-Even mild fatty liver or hepatitis B/C increases risk.

- Heavy drinkers-More than 14 drinks a week for men, 7 for women.

- People on multiple medications-Especially anticonvulsants, antidepressants, or HIV drugs.

- Women, especially postpartum-Hormonal changes may increase susceptibility.

One study found that 96% of patients who developed serious liver injury were slow acetylators. That’s not coincidence-it’s biology.

What Doctors Should Do

Before starting isoniazid, your doctor should check your liver function with a simple blood test. If your ALT is already more than three times the normal level, they should delay treatment or choose an alternative. During treatment, monitor for symptoms: nausea, fatigue, yellowing skin, dark urine, or abdominal pain. Don’t wait. Get your liver enzymes checked immediately if you notice any of these. The CDC recommends monthly liver tests for asymptomatic patients. But if you’re a slow acetylator, over 50, or have other risk factors, testing every 2-3 weeks is smarter. Stop the drug if:- ALT is more than 5 times the upper limit of normal AND you have symptoms

- ALT is more than 8 times normal, even without symptoms

Never ignore these signs. Most liver damage from isoniazid is reversible-if caught early.

Pyridoxine: The Simple Fix for Nerve Damage

Isoniazid also depletes vitamin B6 (pyridoxine), which can cause nerve damage. About 10-20% of people on isoniazid develop tingling, numbness, or burning in their hands and feet. In slow acetylators and diabetics, that rate jumps to 50%. The fix? Take 25-50 mg of pyridoxine every day. It’s cheap, safe, and prevents neuropathy without interfering with TB treatment. Every patient on isoniazid should get it-no exceptions.

Newer Regimens Are Changing the Game

The future of TB treatment is moving away from isoniazid. The WHO now recommends a 4-month regimen using rifapentine and moxifloxacin instead of isoniazid and pyrazinamide. It’s just as effective, with far less liver risk. For drug-resistant TB, the BPaLM regimen (bedaquiline, pretomanid, linezolid, moxifloxacin) eliminates isoniazid entirely. That’s huge. No isoniazid means no isoniazid-induced liver injury. In high-income countries, these new regimens are becoming standard. But in low-resource areas, isoniazid remains the backbone of treatment because it costs just 3 cents per tablet. In the U.S., the same pill costs over $1.50. That’s why global health efforts still rely on it-but they’re pushing hard for alternatives.What’s on the Horizon?

Scientists are testing ways to protect the liver during isoniazid therapy. One promising candidate is silymarin, the active ingredient in milk thistle. A 2021 Chinese trial showed it reduced liver injury by 27% in patients on isoniazid. It’s not yet standard, but it’s a sign that we’re moving toward safer, targeted approaches. Genetic testing for NAT2 status is available and recommended by the European Medicines Agency-but it’s rarely used in practice. Imagine a future where your doctor checks your DNA before prescribing isoniazid. If you’re a slow acetylator, you get a lower dose, or a different drug. That’s precision medicine-and it’s coming.Bottom Line: Know Your Risk

Isoniazid is still one of the most important drugs in the fight against tuberculosis. But it’s not harmless. Its liver risks are real, predictable, and preventable. If you’re prescribed isoniazid:- Ask if you’re at high risk for liver damage-based on age, alcohol use, or other medications.

- Take pyridoxine daily-no exceptions.

- Know the warning signs: nausea, yellow eyes, dark urine, belly pain.

- Get your liver tested regularly-don’t wait for symptoms.

- Ask your doctor if a shorter, safer regimen is right for you.

There’s no need to fear isoniazid. But you need to respect it. With the right precautions, it can still save your life-without wrecking your liver.

Can isoniazid cause permanent liver damage?

In most cases, no. Liver damage from isoniazid is usually reversible if caught early and the drug is stopped. Studies show 95% of patients recover fully within 4 to 8 weeks after discontinuation. However, if liver injury is ignored and treatment continues, it can lead to acute liver failure, which may require a transplant or be fatal. Early detection is critical.

Is genetic testing for NAT2 status necessary before taking isoniazid?

It’s not required in most countries, but it’s recommended by the European Medicines Agency for high-risk populations. If you’re of African, Asian, or Middle Eastern descent, over 50, or have a history of liver issues, asking for NAT2 testing can help your doctor choose the safest dose or alternative therapy. In places where testing isn’t available, doctors rely on clinical risk factors like age, alcohol use, and other medications to guide decisions.

Can I drink alcohol while taking isoniazid?

No. Alcohol increases the risk of liver damage by activating the same liver enzyme (CYP2E1) that turns isoniazid into toxic chemicals. The CDC advises avoiding alcohol completely during treatment. Even moderate drinking-more than 7 drinks per week for women or 14 for men-significantly raises the chance of severe liver injury. Abstaining is the only safe choice.

Why do I need to take vitamin B6 with isoniazid?

Isoniazid blocks the body’s use of vitamin B6 (pyridoxine), which can lead to nerve damage called peripheral neuropathy. Symptoms include tingling, burning, or numbness in the hands and feet. Taking 25-50 mg of pyridoxine daily prevents this side effect. It doesn’t interfere with isoniazid’s ability to kill TB bacteria-it just protects your nerves. Everyone on isoniazid should take it, especially those with diabetes, kidney disease, or alcohol use.

Are there safer alternatives to isoniazid for tuberculosis treatment?

Yes. For drug-susceptible TB, the WHO now recommends a 4-month regimen using rifapentine and moxifloxacin instead of isoniazid and pyrazinamide. For drug-resistant TB, the BPaLM regimen (bedaquiline, pretomanid, linezolid, moxifloxacin) doesn’t include isoniazid at all. These newer regimens have lower liver toxicity rates and are becoming standard in high-income countries. In low-resource areas, isoniazid remains widely used due to cost, but global health efforts are pushing to expand access to safer alternatives.

15 Comments

Wait, so I just need to take B6 and I'm good? That's it? No big deal.

Let’s be clear: this isn’t ‘risk management’-it’s pharmacological roulette. If your doctor doesn’t test your NAT2 status before prescribing isoniazid, they’re not practicing medicine-they’re gambling with your liver. The data is overwhelming, and yet we still treat this like a coin flip. Shameful.

It is of paramount importance to recognize that the metabolic interplay between isoniazid, rifampin, and pyrazinamide represents a complex pharmacokinetic cascade, wherein the induction of cytochrome P450 enzymes by rifampin significantly amplifies the bioactivation of isoniazid into hepatotoxic intermediates. This phenomenon is not merely an adverse effect-it is a predictable, genotype-dependent metabolic collision that demands individualized therapeutic planning. The fact that this is still not standard of care in many regions is a systemic failure of translational medicine.

They say ‘most people recover’-but what about the ones who don’t? The ones who end up in the ICU with a liver transplant on the horizon? You think that’s just ‘bad luck’? No. It’s negligence wrapped in a clinical guideline.

Everyone on isoniazid should get pyridoxine-period. It’s not optional. It’s not ‘nice to have.’ It’s a non-negotiable part of the prescription. If your provider isn’t prescribing it, ask why. If they can’t give you a solid reason, get a second opinion. Your nerves matter more than their convenience.

i just found out i'm a slow acetylator and now i'm kinda freaked out but also like… wow, this makes so much sense. why didn't anyone tell me this before? i've been taking meds for years and never knew my body was just… slow at cleaning up the mess. thank you for writing this. i feel less alone now.

Alcohol and isoniazid? Don’t even think about it. I’ve seen two people go from ‘just a few drinks’ to liver failure in 3 weeks. It’s not worth it. Zero tolerance. Full stop.

In India, we still rely on isoniazid because it's affordable and accessible, but we also see the highest rates of hepatotoxicity among slow acetylators. We need better screening tools, not just more pills. Genetic testing should be integrated into primary care, not reserved for rich countries. TB doesn’t care about your bank account-why should treatment?

Actually, the 4-month HR regimen isn’t as effective as the 6-month one in real-world settings. You’re trading safety for efficacy-and in places with high TB burden, relapse rates go up. The data from WHO is idealistic. Real patients don’t always complete treatment, and shorter doesn’t always mean better. Don’t oversimplify this.

Let’s not forget-this is not a ‘drug interaction’… it’s a biochemical betrayal. Your own enzymes, manipulated by rifampin, turn a life-saving drug into a slow-acting poison. And we call this ‘standard of care’? We’ve institutionalized metabolic sabotage. The system isn’t broken-it was designed this way. Profit over physiology. Always.

There’s something deeply human here-not just about drugs, but about how we treat bodies we don’t understand. We prescribe like we’re coding a machine, ignoring that we’re working with living, genetic, emotional, alcohol-drinking, sleep-deprived humans. Isoniazid isn’t the villain. Our arrogance is. Maybe the real cure isn’t a new regimen-it’s humility.

So… you’re telling me the solution is to test everyone’s genes, give them B6, and avoid alcohol… and somehow that’s not already standard? Wow. I’m shocked. /s

Let’s be honest-most of this is just rehashing what we’ve known since the 80s. The fact that we’re still having this conversation in 2025 means the medical establishment isn’t listening. Or worse-they’re choosing to ignore it because changing protocols costs money. The science is settled. The politics? Not so much.

Just got my NAT2 results back-slow acetylator. I’m on pyridoxine now, no alcohol, and my liver enzymes are stable. Also, I asked for the 4-month HR regimen and my doctor actually listened. 🙌 You’re not crazy for asking. Fight for your health.

Thanks for the post. I was about to start isoniazid next week. Now I’m getting tested tomorrow. This saved me from a nightmare.