A pterygium isn’t just a spot on your eye-it’s a warning sign. If you’ve ever looked in the mirror and seen a pink, fleshy wedge growing from the inner corner of your eye toward your pupil, you’re not alone. In Australia, where the sun beats down harder than almost anywhere else, about 23% of adults over 40 have it. And it’s not just surfers. Farmers, construction workers, fishermen, even people who walk their dogs in the morning all face the same risk: too much UV light hitting their eyes without protection.

What Exactly Is a Pterygium?

A pterygium is a growth of tissue on the white part of your eye (the sclera) that creeps onto the clear front surface (the cornea). It’s not cancer. It won’t spread inside your body. But if it keeps growing, it can distort your cornea, cause astigmatism, and blur your vision. The name comes from the Greek word for "little wing," because it looks like a tiny wing stretching across your eye. Most often, it starts on the side closest to your nose-about 95% of cases-and grows slowly, sometimes taking years to become noticeable.

It’s not just the color that gives it away. You’ll usually see thin, visible blood vessels running through it. Early on, it might feel like something’s stuck in your eye. Later, it can make your eye red, dry, and irritated. If it reaches your pupil, your vision gets fuzzy. Some people say it feels like looking through a warped piece of plastic.

Why Does the Sun Cause It?

It’s not just being outside. It’s how much UV radiation your eyes absorb over time. Studies show that people living within 30 degrees of the equator have more than double the risk. In Australia, where UV levels regularly hit extreme levels, the numbers are alarming. One study found that if your total UV exposure hits 15,000 joules per square meter over your lifetime, your chance of developing a pterygium jumps by 78%.

Unlike skin, your eyes don’t tan. They don’t send you a warning. The damage builds up silently. A 2021 study from the University of Melbourne tracked outdoor workers and found that those who didn’t wear proper sunglasses had pterygium rates three times higher than those who did. Even on cloudy days, up to 80% of UV rays still get through. Snow, sand, and water reflect UV, making exposure worse. That’s why surfers, skiers, and boaters are at higher risk-and why the condition is nicknamed "Surfer’s Eye."

Pterygium vs. Pinguecula: What’s the Difference?

You might hear your doctor mention "pinguecula" too. It’s common to confuse the two. A pinguecula is a yellowish bump on the white of the eye, usually near the nose. It stays on the conjunctiva-the thin layer covering the sclera-and never grows onto the cornea. Think of it as a warning sign. A pterygium is what happens when that bump starts moving forward, like a vine climbing a fence. About 70% of outdoor workers in tropical areas get pingueculae, but only 30% go on to develop pterygium. The difference? Progression. If it touches your cornea, it’s a pterygium. And that’s when vision problems start.

When Should You Worry?

Not every pterygium needs surgery. Many stay small and cause only mild irritation. But you should see an eye doctor if:

- Your vision becomes blurry, especially when looking straight ahead

- Your eye feels constantly gritty or dry, even with drops

- You can’t wear contact lenses anymore

- The growth is getting bigger, redder, or more noticeable

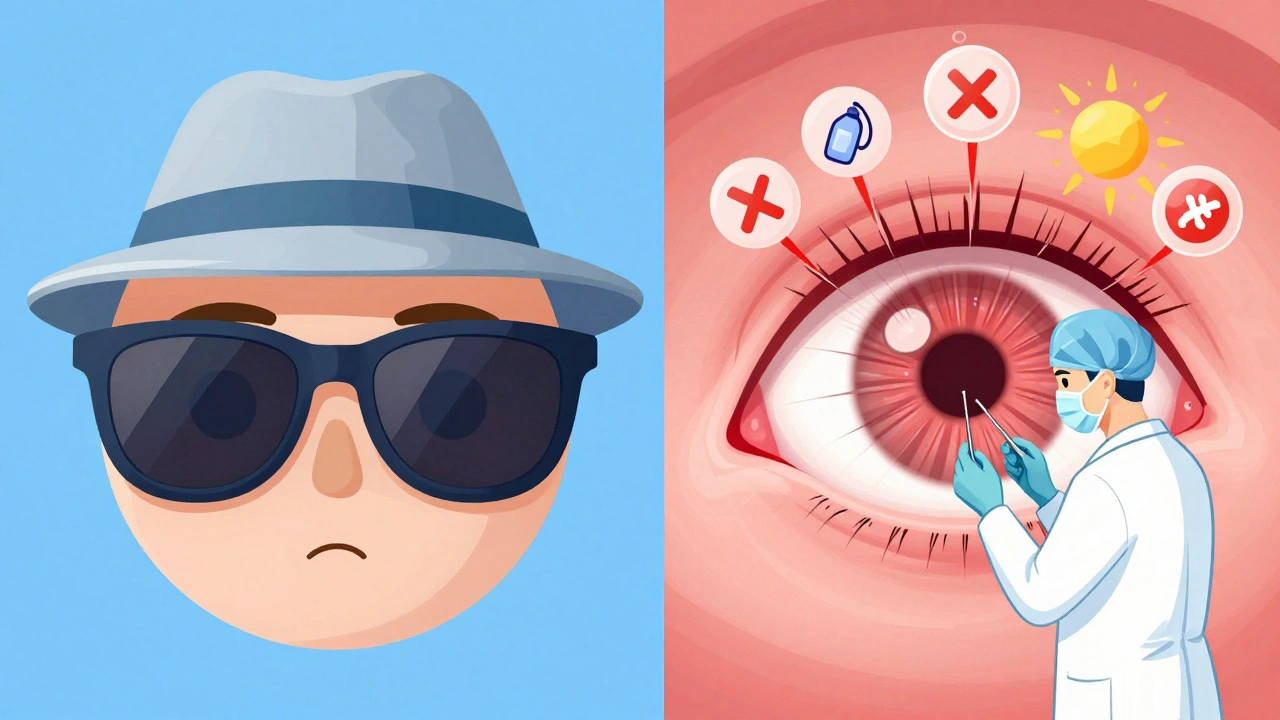

Doctors use a slit-lamp-a special magnifying microscope-to check how far the growth has reached the cornea. No blood tests or scans are needed. It’s all visual. If it’s covering more than 2 millimeters of your cornea, or if it’s starting to change your eye’s shape, treatment becomes urgent.

Surgical Options: What Actually Works?

If your pterygium is blocking your vision or causing serious discomfort, surgery is the only way to remove it. But here’s the catch: without the right technique, it comes back. Up to 40% of simple removals recur. That’s why modern surgery isn’t just about cutting it out.

The gold standard now is conjunctival autograft. The surgeon removes the pterygium, then takes a tiny piece of healthy conjunctiva from another part of your eye-usually near the top-and stitches it over the bare spot. This acts like a bandage and a barrier. Studies show this cuts recurrence to under 10%. Some surgeons add a special drug called mitomycin C during the procedure to kill off any leftover cells that might regrow. That drops recurrence even further-to about 5%.

Another newer option is amniotic membrane transplantation. This uses tissue from a donated placenta, which has natural healing and anti-inflammatory properties. Since June 2023, European guidelines have recommended it as first-line treatment for recurrent pterygium, with success rates hitting 92% in multi-center trials.

There’s also a new method in development: laser-assisted removal. It’s not widely available yet, but early results show it’s faster and causes less bleeding. By 2027, most eye clinics in Australia and the U.S. are expected to offer it.

What’s Recovery Really Like?

Surgery takes about 30 to 45 minutes. You’re awake but numb. Most people go home the same day. But recovery isn’t quick. Your eye will be red, swollen, and sore for 1-2 weeks. You’ll need steroid eye drops for up to 6 weeks to prevent inflammation and scarring. Some patients say the drops are harder to deal with than the surgery itself.

Here’s what patients report:

- 78% say recovery was quicker than expected

- 65% noticed better vision within days

- 42% had discomfort lasting 2-3 weeks

- 37% were unhappy with the redness during healing

One patient on RealSelf.com said: "The surgery took 35 minutes, but the steroid drops regimen for 6 weeks was more challenging than expected." That’s common. The drops sting at first. You have to be strict about timing them. Miss a dose, and inflammation can spike.

How to Stop It Before It Starts

Prevention is the easiest and cheapest treatment. If you live in Australia, or anywhere with high UV levels, protect your eyes every single day-no exceptions.

- Wear UV-blocking sunglasses labeled ANSI Z80.3-2020. They must block 99-100% of UVA and UVB rays.

- Pair them with a wide-brimmed hat. This cuts UV exposure to your eyes by 50%.

- Don’t wait until it’s sunny. UV damage happens even on cloudy days.

- Use lubricating eye drops if your eyes feel dry. New preservative-free options like OcuGel Plus, approved in March 2023, help reduce irritation and slow progression.

One Reddit user, "OutdoorPhotog," shared: "Wearing UV-blocking sunglasses daily has stopped the progression of my early-stage pterygium according to my last two annual check-ups." That’s the power of prevention.

What’s Next for Pterygium Treatment?

Research is moving fast. A Phase II clinical trial (NCT05214387) is testing a topical eye drop called rapamycin. It targets the cells that cause the growth to spread. Early results show a 67% drop in recurrence at 12 months compared to placebo. If approved, this could mean no more surgery for many patients.

Meanwhile, global demand is rising. The pterygium treatment market is worth $1.27 billion today and is expected to hit $1.89 billion by 2028. More people are getting diagnosed because awareness is growing-and because UV exposure is increasing as the ozone layer thins.

But here’s the hard truth: in rural parts of developing countries, only 12% of people can access surgery. In cities of wealthy nations, it’s 89%. That gap isn’t just a statistic-it’s a health crisis.

Final Thoughts

A pterygium isn’t an emergency. But it’s a signal. If you’ve spent years in the sun without eye protection, your eyes are paying the price. The good news? You can stop it. You can treat it. And if it’s caught early, you might never need surgery.

Wear your sunglasses. Get your eyes checked every year. Don’t wait until your vision blurs. Your eyes don’t get a second chance.

Can a pterygium go away on its own?

No, a pterygium won’t disappear without treatment. It may stop growing if UV exposure is reduced, but it won’t shrink or vanish on its own. Once it reaches the cornea, it can only be removed surgically.

Is pterygium surgery painful?

The surgery itself isn’t painful-you’re given numbing drops and sometimes a light sedative. Afterward, your eye will feel sore, gritty, and sensitive to light for a few days. Most people describe it as a burning or scratchy sensation, similar to having sand in the eye. Painkillers and prescribed eye drops help manage this.

Can I still wear contact lenses after surgery?

Most people can return to wearing contact lenses after healing, usually around 4-6 weeks post-surgery. But your eye shape may have changed slightly if the pterygium distorted your cornea. Your optometrist will need to refit your lenses. Some patients find they no longer need contacts at all after surgery because their vision improved.

Are there non-surgical treatments for pterygium?

Yes, but only for mild cases. Lubricating eye drops, anti-inflammatory drops, and UV protection can reduce redness, irritation, and slow growth. However, they won’t remove the tissue. If the growth is affecting your vision or comfort, surgery is the only way to fix it.

How long does it take for a pterygium to grow?

Growth varies widely. Some pterygia stay the same size for decades. Others grow 0.5 to 2 millimeters per year under strong UV exposure. People in tropical climates or with outdoor jobs often see faster progression. Regular eye exams every 6-12 months help track changes before they affect vision.

Can pterygium cause permanent vision loss?

It can, if left untreated. As the tissue grows over the cornea, it can flatten or distort its natural curve, causing astigmatism and blurry vision. In rare, advanced cases, it can block light from entering the eye entirely. That’s why early detection and treatment are critical-permanent damage is avoidable.

14 Comments