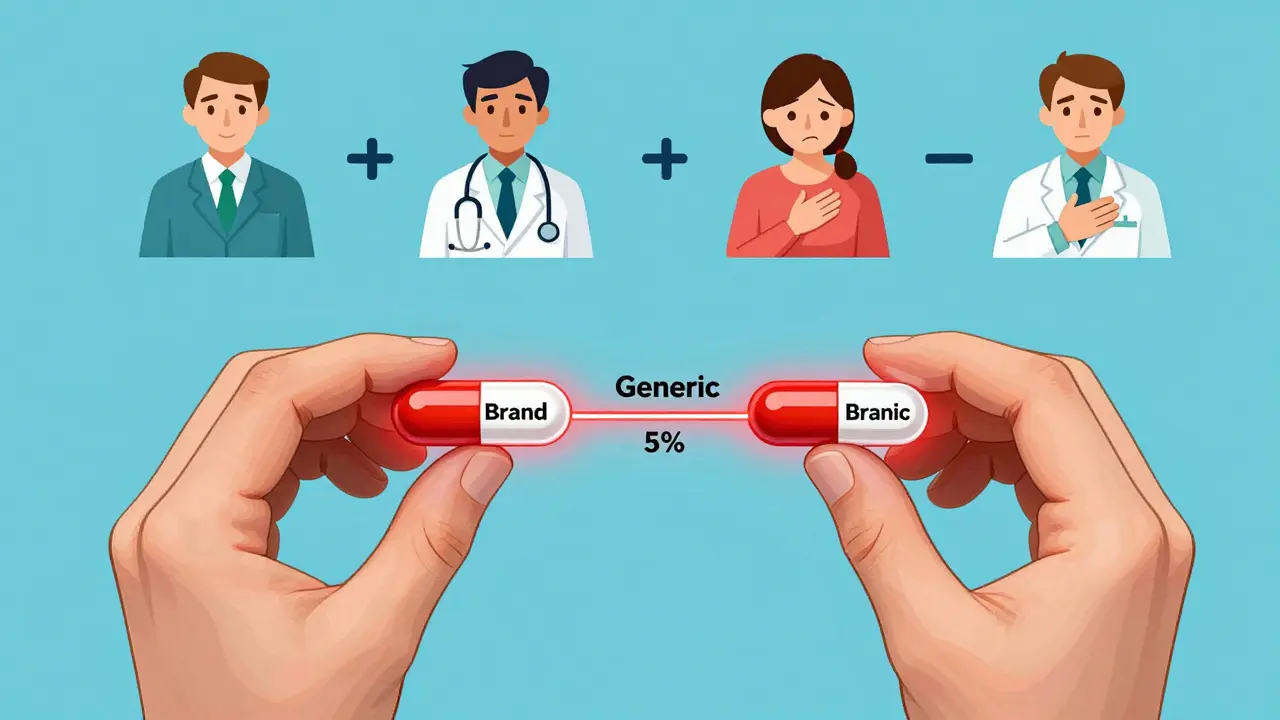

Switching from a brand-name drug to a generic version seems simple: same active ingredient, lower price, same effect. But for some medications, that switch isn’t as straightforward as it looks. When doctors change doses after switching to generics, it’s usually because the drug has a narrow therapeutic index - meaning the difference between a safe dose and a dangerous one is tiny. For these drugs, even small changes in how the body absorbs the medicine can lead to serious problems.

What Makes a Drug High-Risk After a Generic Switch?

Not all generics need dose adjustments. Most people switch without any issues. But certain drugs - called narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs - are different. These are medications where a small change in blood levels can mean the difference between control and crisis. Examples include warfarin (a blood thinner), levothyroxine (for thyroid conditions), phenytoin and carbamazepine (for seizures), and tacrolimus (for organ transplant patients). The FDA defines NTI drugs as those where “small differences in dose or blood concentration may lead to serious therapeutic failures or serious adverse events.” That’s not theoretical. For warfarin, a 10% change in blood levels can trigger a clot or a bleed. For levothyroxine, a slight drop in absorption can cause fatigue, weight gain, and depression - symptoms easily mistaken for other issues. These drugs have very tight windows. The target blood level for warfarin, measured by INR, is usually between 2.0 and 3.0. Go above 4.0? Risk of bleeding. Below 1.8? Risk of stroke. Even a 5% difference in how much drug gets into your bloodstream can push you out of that range.Why Do Generic Versions Sometimes Cause Problems?

All generics must prove they’re bioequivalent to the brand-name drug. That means their absorption in the body must fall between 80% and 125% of the original. On paper, that sounds fine. But for NTI drugs, that 45% range is too wide. Imagine two different generic versions of levothyroxine. One delivers 95% of the expected dose. Another delivers 115%. Both meet FDA standards. But if you switch from one to the other - even if both are “equivalent” - your body gets a different amount. That’s enough to throw off your TSH levels. One study found 23% of patients switching between generic warfarin brands needed a dose adjustment within 30 days. Another found 18.7% of transplant patients on tacrolimus needed a dose change within two weeks of switching generics. It’s not about quality. It’s about consistency. Generic manufacturers use different fillers, coatings, and manufacturing processes. For most drugs, that doesn’t matter. For NTI drugs, it does. Even small variations in how fast the pill dissolves or how well it’s absorbed can shift blood levels enough to cause symptoms.Which Drugs Most Often Need a Dose Change?

Some NTI drugs are more likely to cause trouble than others. Based on clinical reports and surveys of pharmacists, these are the top offenders:- Levothyroxine: The most common NTI drug switched. Patients report fatigue, weight gain, cold intolerance, and brain fog after switching. Dose adjustments of 12.5 mcg or more are not uncommon.

- Warfarin: INR levels can swing wildly after a switch. Clinics now routinely check INR within 7-14 days after any generic switch.

- Phenytoin and Carbamazepine: Used for epilepsy. Even small drops in blood levels can trigger seizures. Serum level monitoring is standard after a switch.

- Tacrolimus and Cyclosporine: Critical for transplant patients. A drop in levels can lead to organ rejection. A rise can cause kidney damage or tremors.

- Digoxin: Used for heart rhythm. Too little = ineffective. Too much = life-threatening arrhythmias.

What Should You Do If You’re Switched to a Generic?

If you take one of these high-risk drugs and your pharmacy switches you to a generic - even if your doctor didn’t ask for it - don’t assume everything’s fine. Here’s what to do:- Ask your doctor if your medication is an NTI drug. If yes, ask if you should be monitored after the switch.

- Watch for symptoms. For levothyroxine: fatigue, weight gain, constipation, depression. For warfarin: unusual bruising, nosebleeds, dark stools. For seizure meds: new or worsening seizures.

- Get tested. For warfarin, get an INR check within 7-14 days. For levothyroxine, a TSH test at 6 weeks. For phenytoin or tacrolimus, a blood level test within 2 weeks.

- Don’t switch back and forth. If you’re stable on a specific generic brand, don’t let your pharmacy switch you again. Multiple switches increase risk.

- Know your pill. Keep the original packaging. If your pill looks different, ask why. Don’t take it if you’re unsure.

Why Do Pharmacies Keep Switching If It’s Risky?

The short answer: money. Insurance companies push for the cheapest generic. Sometimes, they force switches even if your doctor didn’t approve it. A 2022 survey found 43.7% of pharmacists had patients switched multiple times in a year because of insurance formulary changes. This creates chaos. One patient might be stable on Generic A. Then their insurance changes and they get Generic B. Then Generic C. Each switch risks instability. Some academic medical centers now have policies blocking automatic switches for NTI drugs. Community pharmacies? Not so much.Is There a Better Way?

Yes. And it’s already happening. The FDA is working on tighter standards. In 2023, they proposed new bioequivalence rules for NTI drugs: instead of 80-125%, they want 90-111%. That’s a big shift. If adopted, it would mean generics for warfarin or levothyroxine would have to match the brand much more closely. Some generic makers are already stepping up. Teva’s “TacroBell” tacrolimus product showed 32% less variability than standard generics in head-to-head studies. Aurobindo and other specialty manufacturers are developing “supergenerics” with tighter controls. The goal? Reduce the need for dose adjustments. Dr. Janet Woodcock, former head of the FDA’s drug center, predicted that within five years, we’ll see NTI-specific generic categories with higher quality standards - making switches safer.Bottom Line: Don’t Assume Equivalence

For most medications, generics are safe and effective. But for NTI drugs, “equivalent” doesn’t always mean “identical in effect.” If you’re on one of these drugs, your dose isn’t just a number - it’s a balance. And switching generics can tip it. Talk to your doctor before any switch. Ask: “Is this an NTI drug?” If yes, insist on monitoring after the switch. Don’t wait for symptoms to get worse. A simple blood test can prevent a hospital visit. And if your pharmacy switches your medication without warning? Call your doctor. Ask them to write “Do Not Substitute” on your prescription. It’s legal. It’s your right. And for some people, it’s the difference between feeling okay - and feeling dangerously unwell.Do all generic drugs need dose adjustments?

No. Only drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI) - like warfarin, levothyroxine, phenytoin, tacrolimus, and digoxin - often require monitoring or dose changes after switching. For most medications, such as antibiotics or blood pressure pills, generics work just as well without any adjustment.

Can I switch back to the brand-name drug if the generic makes me feel worse?

Yes, but it depends on your insurance. If you’re experiencing side effects or loss of control after switching, your doctor can write a letter of medical necessity to your insurer requesting the brand-name version. Many insurers approve this for NTI drugs if there’s documented evidence of instability.

How long after switching should I get my blood tested?

For warfarin: within 7-14 days. For levothyroxine: at 6 weeks. For antiepileptic drugs like phenytoin or carbamazepine: within 2 weeks. For tacrolimus or cyclosporine: within 10-14 days. These timelines are based on how long it takes your body to reach a new steady state after the switch.

Why do some people have no issues after switching?

Because everyone’s body absorbs medication differently. Some people are naturally more consistent in how they process drugs. Others are more sensitive to formulation changes. If you’ve switched before without problems, you might be one of the majority who don’t need a change. But that doesn’t mean you won’t need one next time - especially if you switch to a different generic manufacturer.

Can my pharmacist tell me which generic I’m getting?

Yes. Ask for the manufacturer’s name on the label. If it’s different from your last fill, that’s a switch. Write it down. If you’re on an NTI drug, tell your doctor about any change in manufacturer - even if you feel fine. Small differences matter.

10 Comments

So let me get this straight - we’re trusting bioequivalence ranges that allow for a 45% swing in absorption for drugs where 5% can kill you? 🤔

That’s not science. That’s regulatory gambling with people’s lives.

And yet, the FDA still calls this ‘acceptable.’

Meanwhile, my TSH went from 2.1 to 6.8 after a pharmacy switch. No one believed me until I showed the lab results.

It’s not ‘all in my head.’ It’s pharmacokinetics.

They treat NTI drugs like ibuprofen.

It’s not even negligence - it’s systemic apathy wrapped in a white coat.

And don’t get me started on insurance formularies forcing switches every quarter.

My doctor’s office gets a new generic every time the pharmacy’s contract expires.

It’s a revolving door of instability.

And we’re supposed to be grateful for the ‘savings’?

Save my life first. Then save me $12.

Also, ‘generic’ doesn’t mean ‘identical.’ It means ‘legally close enough to not get sued.’

Dear colleagues,

It is with profound concern - and a modicum of exasperation - that I respond to the preceding commentary.

While the tone may be perceived as... impassioned, the substance is undeniably valid.

Pharmaceutical equivalence, as currently defined, is a statistical fiction when applied to narrow therapeutic index agents.

One must consider not only bioavailability, but inter-individual variability, gastric pH, food interactions, and even gut microbiome differences.

It is not unreasonable to suggest that, for these medications, a ‘generic’ should be required to demonstrate within-subject consistency - not just population-level equivalence.

Further, the notion that patients should ‘adapt’ to each new formulation is not only impractical - it is ethically indefensible.

Let us not mistake cost-efficiency for clinical wisdom.

Sincerely,

Kristie Horst, PharmD, MS (Clinical Pharmacology)

OMG YES I WAS JUST TALKING ABOUT THIS LAST WEEK!!

My mom switched from brand levothyroxine to generic and started crying for no reason, couldn’t get out of bed, gained 15 lbs in 3 weeks.

Doctor said ‘it’s the same thing’ like it was a different flavor of yogurt.

Finally got her back on the brand after 3 months of misery.

And now my insurance won’t cover it again unless I ‘try’ another generic.

Like my mom’s thyroid is a beta tester for Big Pharma’s budget line.

Also - if your pill looks different, ASK. Seriously. Write down the name on the bottle. It matters.

Don’t let them gaslight you.

❤️❤️❤️

You’re all missing the point.

It’s not about generics.

It’s about the FDA’s entire regulatory framework being designed in the 1980s for a world without pharmacogenomics.

They still use AUC and Cmax as proxies for clinical outcomes - as if bioavailability = efficacy.

But we now know that CYP2C9 polymorphisms alter warfarin metabolism by 40%.

And that levothyroxine absorption is affected by gastric emptying time, which varies by 30% between individuals.

So when you switch generics, you’re not just changing fillers - you’re changing the pharmacodynamic equation.

And no one’s doing TDM for 90% of patients.

It’s not a flaw in generics.

It’s a flaw in the system that treats everyone like a textbook case.

Also - if you’re on tacrolimus and your pharmacy switches you without telling you - sue them.

It’s malpractice.

My brother had a kidney transplant. Switched from brand to generic tacrolimus. His levels dropped 30%. Rejection in 11 days.

He’s fine now. But he almost died because the pharmacy didn’t notify his team.

Doctors don’t know what generic they’re prescribing. Pharmacists don’t know what the patient is taking.

It’s a fucking mess.

Insist on the brand. Write ‘Do Not Substitute’ on the script. It’s legal. Do it.

And if your INR jumps after a switch - go get tested. Don’t wait.

That’s not paranoia. That’s survival.

Stop trusting the system.

Protect yourself.

They’re testing us.

It’s not about money.

It’s about control.

Big Pharma and the FDA are running a slow-motion experiment on millions of people.

They want to see how long we’ll tolerate instability before we revolt.

They know the data. They know the risks.

They just don’t care.

And now they’re pushing ‘supergenerics’ like it’s a win.

It’s not.

It’s a PR move.

They’ll still switch you to a cheaper one next month.

And next year.

And next decade.

They’re not fixing the system.

They’re just making the lie look prettier.

And you? You’re the lab rat.

Don’t forget that.

I’m a nurse and I see this every single week.

Levothyroxine patients coming in with TSH >10, saying ‘I just feel off’ - and their doctor says ‘maybe you’re just stressed.’

But when we check the script - bingo - switched to a new generic last week.

One blood test. 15 minutes. $25.

And it fixes everything.

Don’t let anyone tell you it’s ‘all in your head.’

Your body knows.

Trust it.

And tell your doctor you want your levels checked after any switch.

You deserve to feel like yourself again.

💖 You’re not crazy. You’re just being ignored.

As someone from India where generics dominate healthcare, I can confirm - this issue is global.

Even in our public hospitals, we see patients on phenytoin with breakthrough seizures after switching to local generics.

But here’s the twist: in the U.S., at least you have the option to demand the brand.

In many countries, you don’t even get a choice.

So while your frustration is valid - remember, you still have more power than most.

Use it.

And yes - the FDA’s proposed 90-111% range is a step forward.

But it’s still not perfect.

Let’s push for personalized dosing protocols next.

Not just ‘better generics’ - but ‘right generics for you.’

Thank you for raising this.

It matters.

I’m so glad this thread exists.

I used to think I was just ‘bad at managing my health’ because I felt awful after switching to generic carbamazepine.

Turns out - I had 3 seizures in 10 days.

My neurologist was shocked.

Turns out my pharmacy switched me twice in 3 months.

Now I keep the pill bottle as proof.

I show it to my doctor.

I call the pharmacy if it changes.

And I tell every person I know who’s on an NTI drug: don’t be quiet.

It’s not your fault.

You’re not ‘difficult.’

You’re just paying attention.

And that’s the most powerful thing you can do.

❤️

There is a philosophical undercurrent here that deserves attention.

Medicine, at its core, is an art of individualized care - yet the system has been engineered for mass scalability.

Generics serve an essential function in reducing cost and increasing access.

But when that access comes at the expense of physiological fidelity - particularly for life-sustaining medications - we must ask: what are we optimizing for?

Profit? Efficiency? Or health?

The answer, unfortunately, is often the former.

Perhaps the solution lies not in eliminating generics - but in creating tiers.

Standard generics for low-risk drugs.

High-fidelity generics for NTI agents.

And mandatory monitoring protocols.

It is not unreasonable to demand that the most vulnerable among us be treated with the greatest precision.

It is, in fact, the minimum standard of care.