When your eye doctor says they need to take images of your retina, it might sound like something out of a sci-fi movie. But these tools - OCT, fundus photos, and angiography - are everyday parts of modern eye care. They don’t just give pretty pictures. They reveal what’s happening beneath the surface of your eye, often before you even notice symptoms. For conditions like diabetic eye disease, macular degeneration, or retinal blockages, these tests can mean the difference between keeping your vision and losing it.

What Is OCT, and Why Does It Matter?

Optical Coherence Tomography, or OCT, is like an ultrasound for your eye - but it uses light instead of sound. It creates detailed cross-sections of the retina, the thin layer at the back of your eye that turns light into signals your brain understands. Think of it as a 3D map showing every layer: the nerve fibers, the photoreceptors, the fluid pockets, even tiny scars or swelling.

Modern spectral-domain OCT (SD-OCT) can see details as small as 5 to 7 micrometers. That’s thinner than a human hair. Swept-source OCT (SS-OCT), the newer version, goes even deeper and faster, capturing up to 400,000 scans per second. This means it can show not just the retina, but also the choroid - the layer beneath it that feeds blood to the retina.

Doctors use OCT to track changes over time. If you have macular edema from diabetes, OCT measures how much fluid is building up. If you have age-related macular degeneration, it shows if abnormal blood vessels are growing under the retina. Even something as simple as a macular hole - a tiny tear in the center of your vision - shows up clearly on OCT. And unlike older methods, it’s completely non-invasive. No drops, no needles, no waiting.

Fundus Photography: The Classic Snapshot

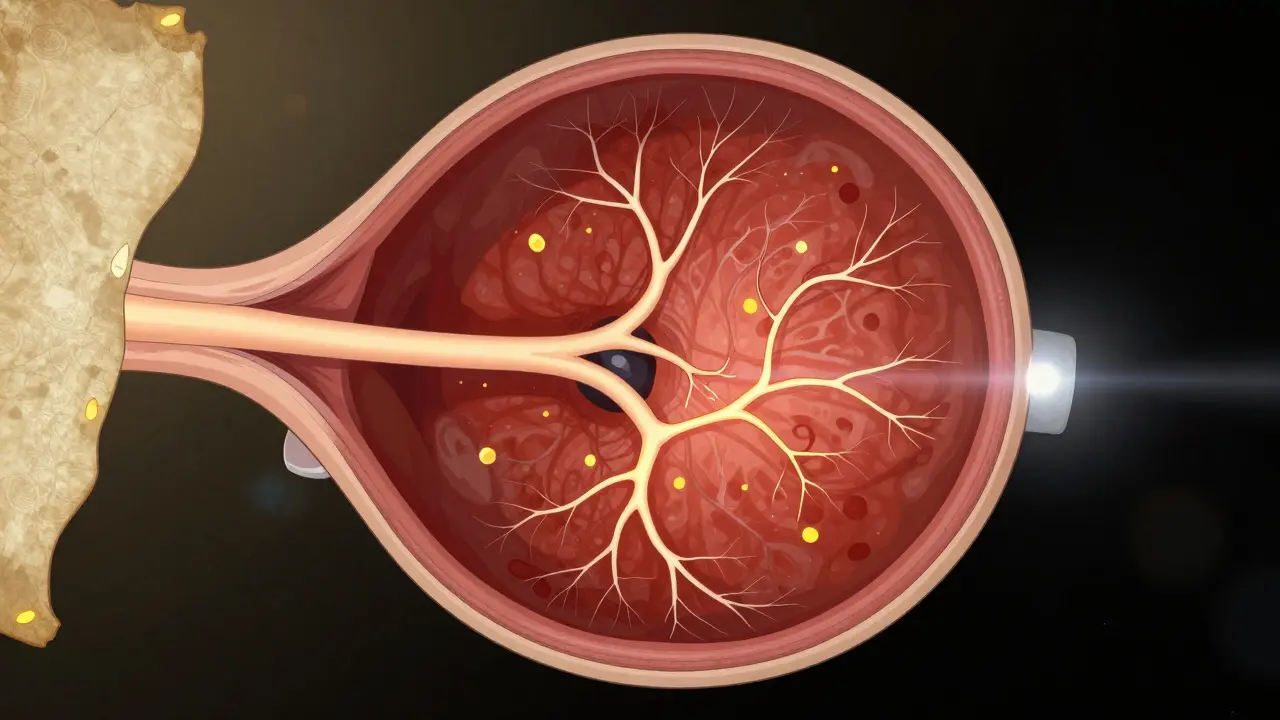

Fundus photography has been around for decades. It’s essentially a high-res photo of the back of your eye. Special cameras, like the Zeiss FF 450+, capture the optic nerve, the macula, the blood vessels, and the retina in one shot. It’s the go-to tool for spotting signs of diabetic retinopathy - those tiny bleeds, swollen vessels, or fatty deposits called exudates.

Why is this still used when we have OCT? Because sometimes, you need the big picture. OCT shows layers in detail, but fundus photos show how everything connects across the whole retina. A doctor can see if a blood vessel is twisted, if the optic nerve looks pale (a sign of damage), or if there’s a pattern of leakage that suggests a blockage.

It’s also great for monitoring. If you’ve been diagnosed with glaucoma or retinal disease, your doctor might take a fundus photo every year. Comparing them side by side shows if things are getting worse - or if treatment is working.

Fluorescein Angiography: The Dye Test

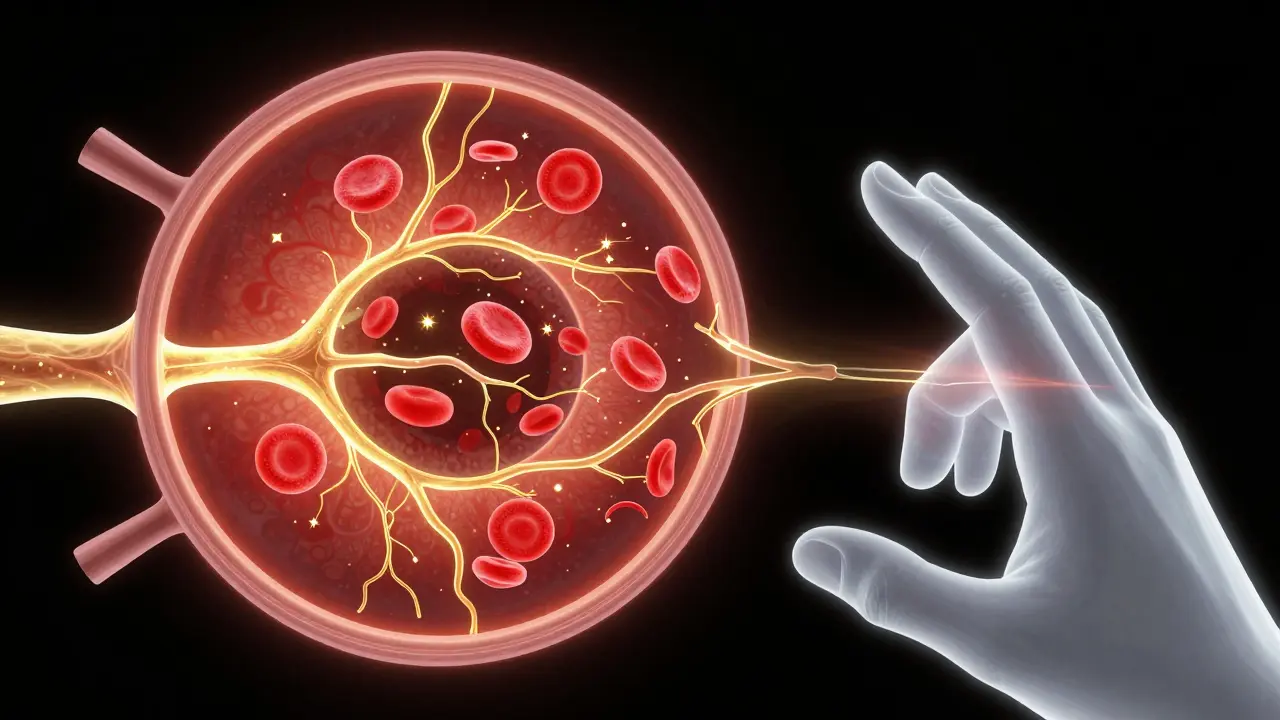

Fluorescein angiography (FA) is the only one of these three that involves a needle. A fluorescent dye is injected into your arm, and as it flows through the blood vessels in your eye, a camera takes rapid-fire photos. The dye lights up under blue light, making the vessels glow like neon signs.

This test reveals leaks. It shows where blood vessels are damaged, where fluid is oozing into the retina, or where new, abnormal vessels are forming. In diabetic retinopathy, FA is still the gold standard for spotting early leaks that OCT might miss. In retinal vein occlusions, it shows exactly where the blockage is and how much of the retina is being starved of blood.

But it’s not perfect. The dye can cause nausea, flushing, or, rarely, an allergic reaction. It takes 10 to 30 minutes. And because it’s a 2D image, it can’t show depth like OCT can. You see the vessels, but not whether the leak is above or below the retina.

OCT Angiography: The Game-Changer

OCT angiography (OCTA) is the newest player. It doesn’t need dye. Instead, it uses OCT technology to detect blood flow by spotting tiny movements in red blood cells. The result? A 3D map of the retina’s blood vessels - layer by layer.

Unlike FA, which gives you one flat image of the whole network, OCTA breaks it down into three distinct layers: the superficial capillaries, the deep capillaries, and the choriocapillaris (the tiny vessels under the retina). This lets doctors see exactly where blood flow is slowing down or stopping - something FA can’t do.

Studies show OCTA is better than FA at detecting early signs of disease. In diabetic patients, it spots tiny areas of non-perfusion - patches where capillaries have shut down - before they cause visible damage. In rare conditions like punctate inner choroidopathy (PIC), OCTA found areas of blood flow loss that traditional imaging missed entirely.

It’s faster, too. A full OCTA scan takes seconds. No waiting for dye to circulate. No risk of allergic reactions. But it’s not foolproof. If you move your eye even slightly, the image blurs. People with cataracts or dry eyes sometimes can’t get clear scans. And OCTA can’t show leakage - only blood flow. That’s why many doctors still use FA alongside it.

How Do These Tests Compare?

Each tool has its strengths. Here’s how they stack up:

| Feature | OCT | Fundus Photography | Fluorescein Angiography (FA) | OCT Angiography (OCTA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| What it shows | Retinal layers, fluid, thickness | Overall retinal structure, vessels, optic nerve | Blood vessel leaks, blockages, abnormal vessels | 3D blood flow, capillary networks, perfusion |

| Invasive? | No | No | Yes (IV dye) | No |

| Scan time | 5-10 seconds | 5-15 minutes | 10-30 minutes | 5-20 seconds |

| Best for | Macular edema, holes, thickness changes | Diabetic changes, optic nerve damage | Leakage, neovascularization, vein occlusions | Early capillary loss, microvascular changes |

| Limits | Can’t show leaks or blood flow | 2D only, no depth | Risky, slow, subjective | Artifacts from movement, can’t detect leakage |

Most eye clinics now use a combination. OCT for structure. Fundus photos for the big picture. FA or OCTA for blood flow. Together, they give a full story.

Real-World Examples

Take Coats disease - a rare condition where abnormal blood vessels leak fluid into the retina. Fundus photos show the white, fatty deposits. FA shows where the leak is. But OCT? It reveals something no other test can: tiny pockets of fluid under the retina, cholesterol crystals in the layers, and even hyperreflective dots that match immune cells from past damage. That’s how doctors know if the disease is active or just scarred.

Or consider diabetic retinopathy. A patient might have blurry vision. OCT shows fluid under the macula. FA shows leaking vessels. OCTA shows that capillaries in the center of the retina have shut down - even before new vessels form. All three together tell the doctor: this isn’t just early diabetes. It’s progressing fast. Treatment needs to start now.

What’s Next?

Artificial intelligence is starting to help interpret these images. Some systems can now flag areas of non-perfusion on OCTA, measure fluid volume in OCT scans, or compare fundus photos year-over-year automatically. But human eyes still matter most. No algorithm can replace a doctor who’s seen thousands of scans and knows what normal looks like - and what’s just noise.

For now, the best approach is simple: use the right tool for the job. OCT for structure. Fundus photos for context. FA for leaks. OCTA for blood flow. Together, they give doctors a window into your eye that wasn’t possible 20 years ago. And for people at risk of vision loss, that window could mean everything.

Is OCT safe? Does it hurt?

Yes, OCT is completely safe and painless. No radiation, no contact with your eye, and no drops needed. You just sit in front of the machine, look at a light, and stay still for a few seconds. It’s like having a quick photo taken - but of the inside of your eye.

Why do I need fluorescein angiography if OCT is better?

OCT shows structure, but not leakage. Fluorescein angiography is still the best way to see where fluid is leaking from blood vessels - especially in diabetic eye disease or retinal vein blockages. They’re not competitors; they’re teammates. OCT tells you how much fluid is there. FA tells you where it’s coming from.

Can OCTA replace fluorescein angiography?

In some cases, yes - especially for tracking capillary loss or early neovascularization. But OCTA can’t detect leakage, which is critical in conditions like macular edema or retinal vein occlusion. Most experts still recommend using both. OCTA for blood flow, FA for leaks. The combination gives the full picture.

How often do I need these tests?

It depends on your condition. If you have diabetes, you might get OCT and fundus photos once a year. If you have macular degeneration, you might need OCT every 3-6 months. For active disease, like new blood vessel growth, doctors may do FA or OCTA more often. Your doctor will tailor the schedule to your needs.

Are these tests covered by insurance?

Yes, in most cases. OCT, fundus photography, and fluorescein angiography are standard diagnostic tools for eye disease and are typically covered by Medicare and private insurance when medically necessary. OCTA is newer, but coverage is expanding rapidly as its value becomes clear.

14 Comments

OCT is the closest thing we have to a non-invasive biopsy of the retina. The fact that we can now visualize individual photoreceptor layers in vivo is nothing short of revolutionary. Twenty years ago, we were guessing based on symptoms and static images. Now we're measuring subcellular changes over time. That's not just progress-it's a paradigm shift in how we understand retinal disease.

Let me tell you something-OCTA is overhyped. Everyone’s chasing the shiny new toy while ignoring the fact that FA still catches what OCTA misses: leakage. I’ve seen patients with diabetic maculopathy where OCTA showed perfect perfusion, but FA revealed a massive capillary dropout that was already causing irreversible damage. You don’t replace gold standard with a pretty 3D render. This is medicine, not a video game.

Y’all are underestimating how much these tools are saving sight. I work in a rural clinic-we don’t have specialists flying in every week. But with OCT and fundus photos, we can catch diabetic changes before someone loses their vision. One lady came in thinking she just needed new glasses. OCT showed early macular edema. We started her on treatment. Two years later? She’s still driving. That’s the real win. No fancy jargon needed-just good tech in the right hands.

India has been doing retinal imaging for decades with basic equipment. Why are Western clinics acting like OCTA is some divine revelation? We had portable fundus cameras in rural clinics before you were born. You’re not innovating-you’re repackaging. And don’t get me started on the cost. These machines are priced like luxury cars. Who exactly is this for? The 1% who can afford it?

FA is still the MVP for active disease. I’ve had patients where OCTA looked clean but FA lit up like a Christmas tree-leaks everywhere. And yes, the dye’s uncomfortable, but it’s a 10-minute ordeal that can prevent blindness. The trade-off is worth it. Also, if you think OCTA is perfect, you haven’t seen the artifacts from a patient who blinked. One twitch and your whole scan is garbage. FA? You get the full story, even if it’s messy.

Let’s cut through the marketing fluff. OCTA is not a replacement for FA. It’s a supplement. And even then, it’s unreliable in patients over 60 with cataracts or dry eyes-which is like 80% of the population we’re trying to screen. The real problem? Clinics are buying OCTA machines because they’re trendy, not because they’re clinically superior. Meanwhile, patients are getting scanned twice, billed twice, and still missing critical leaks because someone thought ‘newer = better.’ This isn’t innovation. It’s corporate greed disguised as progress.

These tools are not competitors. They are partners. Each one reveals a different dimension of retinal health. Think of them as different lenses on the same camera. OCT shows the structure. Fundus shows the landscape. FA shows the leaks. OCTA shows the flow. Together, they create a complete picture. No single tool can do it all. And that’s not a weakness-it’s precision.

It’s fascinating how technology has shifted the diagnostic paradigm from reactive to preemptive. Twenty years ago, we waited for symptoms. Now we detect microvascular changes before patients even notice blurred vision. The data is no longer anecdotal-it’s quantifiable. We can measure fluid volume, track capillary density, and correlate findings with long-term outcomes. That’s the real power of modern ophthalmology.

i just had my first oct scan and it was so cool. i didnt even feel anything. the tech said it was like a camera for the inside of my eye. i was nervous but it was quick and easy. now i know why my doc wanted to do it. my grandma lost her sight and i dont want that. this feels like hope.

Oh wow, you mean we’re not just taking pretty pictures? I thought this was all for Instagram. Next you’ll tell me these scans actually help people. How quaint.

Every tool has its soul. OCTA is like poetry-it reveals the hidden rhythm of blood flow. FA is the raw truth, bleeding out in fluorescent hues. Fundus is the portrait of the retina’s soul. And OCT? It’s the anatomy textbook in motion. We don’t choose one-we honor all. The eye doesn’t speak in binaries. Why should we?

My uncle’s a diabetic and he swears by the yearly fundus pics. Said it caught something before he even knew he had a problem. Honestly, I didn’t think much of it till I saw the images. Like seeing your own organs for the first time. Wild. And no dye? Sign me up. OCT’s the future, no cap.

FA still matters. End of story.

Perhaps we are too quick to elevate technology above intuition. The eye has always been a mirror-not just of disease, but of the body’s deeper rhythms. OCT, FA, OCTA-they are instruments, yes, but they are not the physician. The physician listens. The physician observes. The technology merely amplifies what the trained mind already senses. Do not mistake the map for the territory.