Graves’ disease isn’t just an overactive thyroid. It’s your immune system turning against you. Instead of protecting your body, it sends out rogue antibodies that trick your thyroid into pumping out too much hormone. This isn’t a temporary glitch - it’s a chronic autoimmune condition that affects how your heart beats, how you sleep, how much weight you lose, and even how your eyes look. About 80% of all hyperthyroidism cases in the U.S. are caused by Graves’ disease, and it hits women seven times more often than men, especially between ages 30 and 50.

What Happens When Your Immune System Attacks Your Thyroid

Your thyroid is a small butterfly-shaped gland at the base of your neck. It controls your metabolism - how fast you burn energy, how warm you feel, how quickly your heart beats. In Graves’ disease, the immune system produces something called thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin (TSI), or TRAb. These antibodies latch onto the same receptors that TSH (thyroid-stimulating hormone) normally binds to. But instead of being regulated by your brain, your thyroid goes into overdrive. It doesn’t care if you’ve had enough hormone - it just keeps making more.

That leads to classic signs: rapid heartbeat, shaky hands, weight loss even when you’re eating more, trouble sleeping, and intense anxiety. Many people think they’re just stressed or going through menopause. In fact, nearly half of patients report being misdiagnosed for months - some for over a year. Blood tests are the only way to know for sure. If your TSH is below 0.4 mIU/L and your free T4 is above 1.8 ng/dL, you’re likely hyperthyroid. But what makes it Graves’? The presence of TRAb antibodies. These are detected in 90-95% of cases and are the gold standard for diagnosis.

The Three Faces of Graves’ Disease

Graves’ doesn’t just mess with your metabolism. It has three signature features:

- Hyperthyroidism: The core problem - too much thyroid hormone.

- Graves’ ophthalmopathy: Eye swelling, bulging, redness, double vision. Around 30-50% of patients get this. In 3-5%, it threatens vision due to pressure on the optic nerve.

- Dermopathy: Rare - only 1-4% of cases - but causes thick, red skin on the shins or tops of feet. It’s called pretibial myxedema.

Eye symptoms can appear before, during, or even after thyroid levels are controlled. That’s why managing Graves’ isn’t just about pills - it often needs a team: an endocrinologist, an ophthalmologist, and sometimes a radiation oncologist. If your eyes are bulging or painful, don’t wait. Early treatment with IV steroids or orbital radiotherapy can prevent permanent damage.

Why PTU? The Role of Propylthiouracil in Treatment

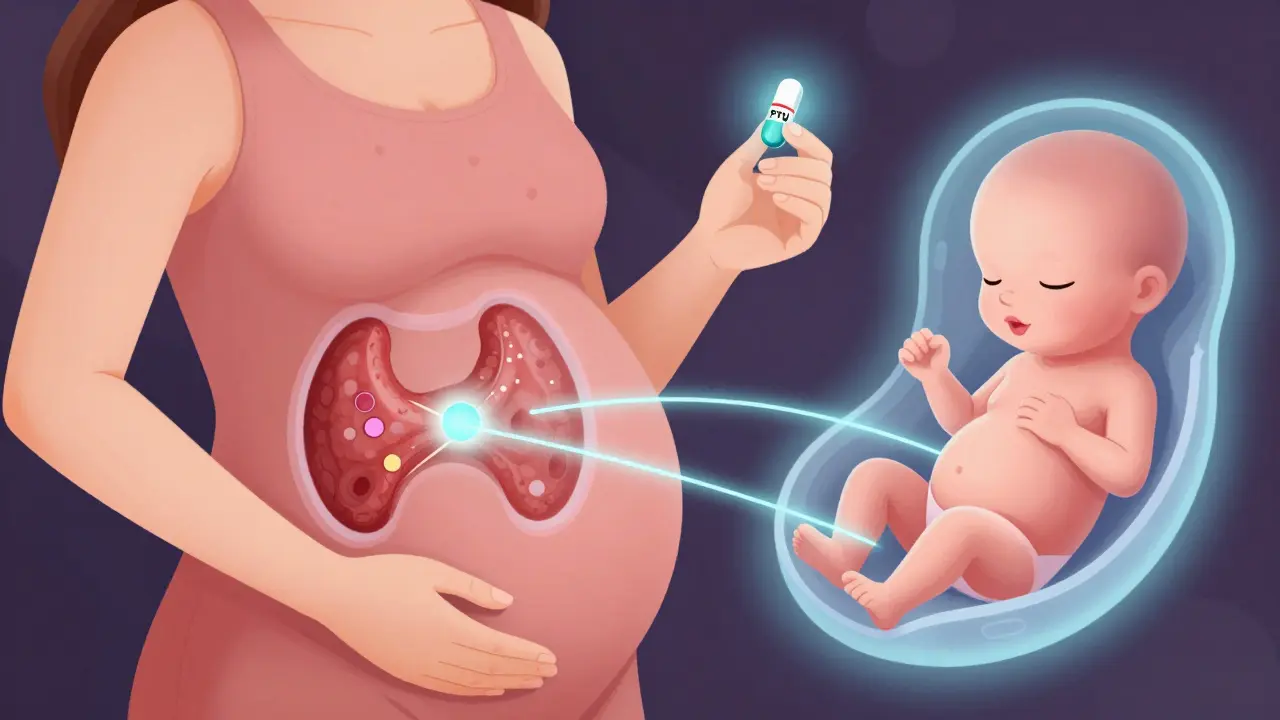

There are three main ways to treat Graves’ disease: antithyroid drugs, radioactive iodine, and surgery. Antithyroid drugs are usually the first step. Two are commonly used: methimazole and propylthiouracil (PTU). Methimazole is preferred for most adults - once daily, fewer side effects, better long-term safety. But PTU has one critical advantage: it’s safer in early pregnancy.

Why? Because methimazole can cause rare but serious birth defects if taken in the first trimester. PTU doesn’t cross the placenta as easily, making it the go-to drug for pregnant women in the first 12 weeks. That’s why doctors still prescribe it - even though it carries a higher risk of liver damage. About 0.2-0.5% of patients on PTU develop severe liver injury, sometimes leading to liver failure. That’s why monthly liver function tests are mandatory. If you start feeling nauseous, yellowing of the skin, or right-sided abdominal pain, stop the drug and call your doctor immediately.

PTU dosing starts at 100-150 mg three times a day. For severe cases or thyroid storm (a life-threatening surge of hormones), doses can go as high as 800 mg daily. It works faster than methimazole, which is why it’s also used in emergencies. But it’s not a long-term solution for most people. After the first trimester, doctors usually switch patients back to methimazole.

How PTU Compares to Other Treatments

Here’s how the options stack up:

| Treatment | Effectiveness | Side Effects | Long-Term Outcome | Cost (Monthly Estimate) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTU (Propylthiouracil) | High (controls hormones in 3 months) | Liver toxicity (0.2-0.5%), taste changes, joint pain | 30-50% remission after 12-18 months | $10-$30 |

| Methimazole | High (once daily) | Skin rash, joint pain (0.1-0.3%), rare liver issues | 30-50% remission; higher relapse if stopped | $10-$50 |

| Radioactive Iodine (I-131) | 80-90% cure rate | Permanent hypothyroidism (50-80% within a year) | Requires lifelong levothyroxine | $300-$1,500 (one-time) |

| Thyroidectomy (Surgery) | 95% success | Damage to vocal cords (1%), low calcium (1-2%) | Permanent hypothyroidism | $5,000-$15,000 |

Radioactive iodine is the most common long-term fix in the U.S. It destroys thyroid tissue, stopping hormone overproduction. But it almost always leads to hypothyroidism - meaning you’ll need to take thyroid hormone pills for the rest of your life. Surgery is fast and definitive, but it’s invasive. Most people start with drugs because they’re reversible and don’t require permanent changes.

What Happens After Treatment?

Even if your thyroid levels return to normal, the disease isn’t always gone. About 30-50% of patients go into remission after 12-18 months of antithyroid drugs. But 40-60% relapse within a year of stopping medication. That’s why doctors don’t just check your TSH once and call it done. They track TRAb levels. If your antibody levels are still high after treatment - above 10 IU/L - your chance of relapse is 80%. That’s a clear signal to keep going or consider a different path.

And even if your thyroid is under control, your eyes might not be. Around 40% of patients still have eye symptoms after hormone levels normalize. Some need steroids, radiation, or even surgery to protect their vision. This is why Graves’ disease isn’t just an endocrine issue - it’s a whole-body condition.

Who’s at Risk, and Why?

Graves’ disease doesn’t come out of nowhere. Genetics play a huge role - twin studies show a 79% heritability rate. If your mom or sister had it, your risk jumps. Women are far more likely to get it, especially after pregnancy. About 5-10% of women develop Graves’ in the year after giving birth. Smoking doubles your risk of severe eye disease. Stress and infections can trigger it, too.

Geographically, it’s rare in China (39 cases per 100,000 people) and common in Finland (453 per 100,000). Why? Likely a mix of genes, environment, and vitamin D levels. We don’t fully understand it yet - but we know who’s vulnerable.

What’s New in Treatment?

The treatment landscape is changing. In 2021, the FDA approved teprotumumab - the first drug specifically for Graves’ eye disease. It’s not a cure, but it reduces bulging eyes by 71% in clinical trials. The catch? It costs $150,000 for a full course. Most insurance won’t cover it unless you’ve tried everything else.

Researchers are also testing new drugs like K1-70, a TSH receptor blocker that normalizes thyroid function without causing hypothyroidism. Early results are promising. And in labs, B-cell depletion therapy with rituximab is showing remission in 60% of tough cases.

Home monitoring is getting better, too. The FDA approved a thyroid biosensor in 2022 that lets you track TSH from your phone. It’s still mostly in research, but soon, patients may be able to adjust meds without weekly blood draws.

Living With Graves’ Disease

Patients often say the worst part isn’t the physical symptoms - it’s the fear. The heart racing at 130 bpm. The insomnia. The weight loss you can’t explain. The feeling that no one believes you. One patient on a support forum wrote: ‘PTU saved my pregnancy, but the liver checks were torture. My ALT hit 120 - normal is under 40. I cried every time I had to draw blood.’

But there’s hope. Three out of four patients get their thyroid levels under control within three months. With proper treatment, you can live a full life. You can work, travel, have kids. You just need to be vigilant. Know the warning signs: fever, sore throat (signs of agranulocytosis), yellow skin (liver damage), or sudden vision changes. Call your doctor immediately. Don’t wait.

Support matters. The Graves’ Disease and Thyroid Foundation runs a 24/7 helpline. The American Thyroid Association has a directory of 1,200+ specialists. You’re not alone in this.

When to Seek Help

Don’t ignore these red flags:

- Heart rate over 100 bpm at rest

- Temperature above 100.4°F with confusion or vomiting (possible thyroid storm)

- Sudden vision loss or double vision

- Jaundice, dark urine, or severe abdominal pain (signs of liver damage from PTU)

- High fever, sore throat, mouth ulcers (signs of low white blood cells)

Thyroid storm is rare - but deadly. It kills 20-30% of people who don’t get treated fast. If you suspect it, go to the ER. Now.

Is PTU safe during pregnancy?

PTU is the preferred antithyroid drug during the first trimester of pregnancy because it crosses the placenta less than methimazole, reducing the risk of birth defects. After the first 12 weeks, doctors usually switch patients to methimazole due to PTU’s higher risk of liver damage. Always work with an endocrinologist who specializes in pregnancy and thyroid disorders.

Can Graves’ disease be cured?

Graves’ disease can go into remission - about 30-50% of patients stop medication and stay normal for years. But it’s not a guaranteed cure. Relapse is common, especially if thyroid antibodies stay high. Radioactive iodine and surgery eliminate the overactive thyroid, but they cause permanent hypothyroidism, which requires lifelong hormone replacement. So while the hyperthyroidism can be resolved, the autoimmune trigger often remains.

Why does PTU cause liver damage?

The exact reason isn’t fully understood, but PTU can trigger an immune reaction in the liver in susceptible people, leading to inflammation and cell death. This happens in about 1 in 500 users. Risk increases with higher doses and longer use. That’s why monthly liver tests are required - to catch damage before it becomes severe.

How long do I need to take PTU?

For most people, PTU is taken for 12-18 months. In pregnancy, it’s usually stopped after the first trimester. Dosing starts high and is gradually lowered as thyroid levels normalize. Never stop abruptly - your thyroid can surge back. Always follow your doctor’s tapering plan.

Can Graves’ disease come back after treatment?

Yes. Even after successful treatment with drugs, radioactive iodine, or surgery, the immune system can reactivate. Relapse is most common within the first year after stopping antithyroid meds. Regular follow-ups and TRAb testing help predict risk. If antibodies stay high, your doctor may recommend long-term treatment or a more permanent solution.

What’s the difference between Graves’ disease and Hashimoto’s?

Both are autoimmune thyroid diseases, but they do the opposite. Graves’ causes the thyroid to make too much hormone (hyperthyroidism). Hashimoto’s causes the thyroid to be destroyed, leading to too little hormone (hypothyroidism). They can even switch - some people start with Graves’ and later develop Hashimoto’s after radioactive iodine treatment. The antibodies are different: TRAb in Graves’, TPO and TgAb in Hashimoto’s.

If you’ve been diagnosed with Graves’ disease, know this: it’s manageable. It’s not a death sentence. It’s not a life of constant crisis. With the right treatment - whether it’s PTU, methimazole, or another path - you can get back to feeling like yourself. Just don’t go it alone. Find a specialist. Track your symptoms. Ask questions. Your thyroid isn’t just a gland - it’s the engine of your body. Treat it with care.

13 Comments

wait so ptu can cause liver failure?? like... i thought it was just for pregnancy?? my aunt took it and she’s fine but now i’m scared to even look at my thyroid meds

It’s not just about the liver, though-that’s the most dramatic risk. The real tragedy is how often Graves’ is dismissed as ‘just anxiety’ or ‘stress,’ especially in women. I spent 14 months being told to meditate, cut caffeine, and get more sleep-while my heart raced at 120 bpm at rest. The antibodies don’t lie. TRAb testing should be standard for anyone with unexplained tachycardia, weight loss, or tremors. It’s not paranoia; it’s pathophysiology.

Thank you for this comprehensive breakdown. As a clinical pharmacist, I’ve seen too many patients switch from PTU to methimazole during pregnancy without proper counseling. The placental transfer difference is real, but so is the hepatotoxicity risk. I always emphasize: PTU isn’t ‘safer’-it’s ‘less teratogenic in the first trimester.’ That’s a nuanced distinction, and patients deserve clarity. Also, for those considering radioactive iodine: the hypothyroidism isn’t a side effect-it’s the intended outcome. Many don’t realize they’re trading hyperthyroidism for lifelong replacement therapy.

TRAb levels predict relapse better than TSH.

Man, I had Graves’ back in 2018. PTU was hell-taste like metal, constant nausea. But I kept it going because I was trying to get pregnant. My endo was awesome, though. She had me on monthly liver panels and even called me personally when my ALT spiked. I made it through. Now I’m on methimazole and pregnant with twins. It’s messy, but it’s doable.

There’s something deeply human about the way this disease sneaks up on you. It’s not just the physical symptoms-it’s the loneliness of being told you’re ‘too young’ to have this, or ‘too healthy’ to be this sick. I didn’t believe it myself until my eyes started bulging. I thought I was just tired. Turns out, my immune system had been waging war for months. You’re not alone. And yes, you can still have a full life.

They say PTU is safe in pregnancy… but what if the real danger is the system that pushes it? Big Pharma loves a niche drug with a scary warning label. They profit from liver tests, ER visits, and lifelong monitoring. I’ve seen the receipts. The real cure? Stop the autoimmune trigger-diet, gut health, stress reduction. But that’s not profitable, is it?

PTU was designed by the pharmaceutical-industrial complex to keep people hooked. The liver damage? A feature, not a bug. They want you coming back for bloodwork, scans, and ‘follow-ups.’ Meanwhile, the FDA approved teprotumumab at $150K per course-because why cure when you can monetize the eyeballs? The truth is, Graves’ is triggered by fluoride in the water. It’s been proven in Eastern Europe. They just don’t want you to know.

So let me get this straight-we’ve got a drug that can save your baby’s face but might cook your liver… and we call that ‘medicine’? I’d rather have a thyroid storm than a 10% chance of turning into a human liver emoji.

Anyone who says Graves’ isn’t ‘real’ because it’s ‘autoimmune’ is just denying biology. You don’t get to pick which parts of your body your immune system attacks. If your body turns on itself, that’s not weakness-that’s a biological betrayal. And if you’re on PTU and you’re not getting monthly liver panels? You’re playing Russian roulette with your organs. Stop being casual about your health.

I’ve been in remission for 5 years now. No meds. No symptoms. My TRAb is undetectable. But I still check my pulse every morning. Just in case. You never really stop being the person who almost lost their eyesight. Or their life. You just learn to carry it quietly.

It is worth noting that the geographical disparity in Graves’ incidence-Finland versus China-may reflect not only genetic factors but also dietary iodine intake, environmental pollutants, and vitamin D status due to latitude. In India, where I practice, the disease presents later, often with more severe ophthalmopathy, possibly due to delayed diagnosis and limited access to antibody testing. The solution is not merely pharmacological-it is systemic: education, screening, and equitable access to endocrinology care.

USA thinks it’s the center of medical knowledge. PTU? Pfft. In India, we treat Graves’ with ashwagandha, turmeric, and yoga. No liver damage. No $150K drugs. Just ancient wisdom. You think your blood tests are science? We’ve been balancing doshas for 5,000 years. Your ‘gold standard’ is just another Western myth. Wake up.